Nathan Geraci is President of The ETF Store, Inc. and host of the weekly radio show “The ETF Store Show“.

The various reasons why investors continue to pull money out of actively managed mutual funds and invest in ETFs have been well-documented. From the high cost of owning mutual funds to their consistent underperformance to their lack of transparency, mutual fund investors are recognizing that they may not be getting what they pay for. However, another reason investors are shunning mutual funds – and one that doesn’t receive nearly as much fanfare – is the relative tax inefficiency of mutual funds compared to ETFs. While tax savings may not garner the headlines that fund fees and performance do, they can have every bit as significant an impact on your investment returns. As the end of the year approaches, now is the time to review investments held in taxable accounts to avoid an unpleasant surprise come tax time.

Understanding the tax inefficiency of mutual funds compared to ETFs requires some additional explanation (which can be found here), but the bottom line is this: if you invest in ETFs, you have more control over your tax bill. With mutual funds, if you own a particular mutual fund and another shareholder wishes to sell their mutual fund shares, you could be penalized with a taxable capital gain distribution – even though you didn’t take any action. If other investors panic and sell their mutual fund shares during a brief market downturn (like we recently witnessed), that could trigger a taxable event for you. Or, consider the recent departure of Bill Gross from Pimco. According to a recent Reuters article, the flagship Pimco Total Return Fund saw nearly $50 billion in redemptions after Gross’ departure. In order to meet those redemptions, Pimco was forced to sell underlying bonds held by the fund to raise cash to give to shareholders – and bonds have done pretty well over the last few years. By law, any capital gains on those bonds must be distributed to all shareholders. If you hold the Pimco Total Return fund in a taxable account, you are on the hook to pay taxes on those capital gain distributions. So to recap, in this case, because a mutual fund manager decided to switch jobs, you get hit with a tax bill.

There are many other scenarios where a mutual fund could distribute large capital gains – including when your funds have suffered large losses, but they all come down to the structure of the mutual fund. In contrast, if a shareholder wishes to sell shares of an ETF, they simply place a trade on the exchange – typically with no impact on other shareholders. In addition, the ETF structure itself lends to greater tax efficiency because when ETF shares are redeemed, the underlying securities are delivered “in-kind”. This means shares of the underlying stocks are exchanged for shares of the ETF with no taxable event. A benefit of this process is that ETF providers can shed their lowest cost basis shares of stocks (which have the largest capital gains). Mutual funds don’t have this luxury. To be clear, there are instances where ETFs may pay capital gain distributions, including if a wave of selling results in ETF redemptions, but those instances are few and far between and the impact is typically muted compared to mutual funds.

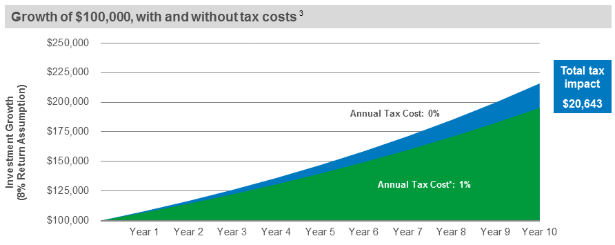

Consider that last year, 99% of iShares ETFs paid no capital gains. iShares is the largest ETF provider in the world, offering nearly 300 U.S.-listed ETFs covering a wide variety of asset classes. And make no mistake about it, taxes can have a big impact on your investment returns as shown in following chart from iShares:

The long-term average annual tax cost for stock mutual funds over the past 10 years was 0.9%. The average annual tax cost for bond funds over the same period was 1.6%.4

3Source: BlackRock. For illustrative purposes only. Does not include commissions or sales charges or fees.

4Source: Morningstar, as of 3/31/14. “Tax cost” is a Morningstar measure of the impact of taxes on capital gains and income distributions on performance. Averages are calculated using the oldest share class of all Open-End Mutual Funds available in the U.S. (excluding municipal bond and money market funds) with 10 year track records as of 3/31/14.

Just a 1% difference in tax cost (note that iShares found the average annual tax cost for a mutual fund was 1.3%), yielded more than a $20,000 difference in your account balance over 10 years! $20,000! And this doesn’t account for any reduction in investment costs by using ETFs or the avoidance of mutual fund manager underperformance.

Over the next several weeks, mutual fund companies will begin reporting 2014 capital gain distributions. Already, many have posted projected capital gain distributions. For example, American Funds, one of the country’s largest mutual fund companies and provider of the popular Growth Fund of America, expects some of their mutual funds to distribute up to 12% of their current share price as a capital gain. If you hold mutual funds set to distribute large capital gains in a taxable account, it might make sense to sell these positions before getting hit with capital gain distributions. If you are looking to purchase a fund in your taxable account, you should check to ensure the fund isn’t set to pay a large capital gain distribution. Perhaps most importantly, if you are not currently investing in ETFs in your taxable account, it may be time to take a closer look. While lower costs and avoidance of active manager underperformance are certainly important, there is nothing worse than paying money to Uncle Sam because of the actions of less disciplined shareholders or a mutual fund manager looking for greener pastures.